What Value Oil?

Gary Matthews

If somebody had told you 15 years ago when oil prices were rising above $150 a barrel that oil producers would be paying storage companies good money to take oil off their hands, what would you have said? For that matter, what would you have said if somebody had told you these things a month ago?

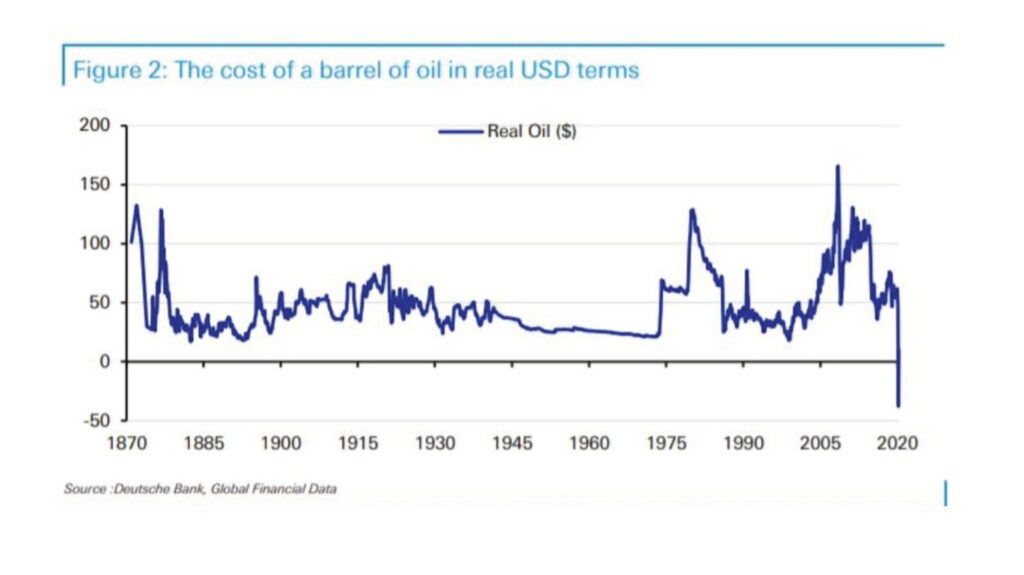

The chart here shows the real, inflation-adjusted price of oil from 1870 to earlier this week, and what you see on the right side is a price collapse of unprecedented proportions. As pandemic-related lockdowns force factories to close and people to stop auto and air travel, global demand for oil has fallen by an amazing 29 million barrels a day. Oil exporters have reduced production, but not by nearly this degree, which means that, until Monday (April 20), they were selling the excess at below-extraction prices to anybody with the storage capacity to accept it. Storage capacity filled up rapidly, so that for a brief time, producers had to pay those who still had room in their storage facilities (via paying people to take their crude oil contracts) up to $40 a barrel to take the oil off their hands. Other producers are leasing tankers at high costs and storing oil at sea—reportedly paying $100,000 per day for each tanker.

As of this writing (April 23), oil’s price is back in positive territory but gyrating wildly. Of course, oil does not actually have a negative worth, at least not yet. Beyond the current pandemic, however, climate change is rapidly changing the price calculus regarding all fossil fuels. SRI investors supporting fossil free portfolios in recent years have been arguing that much of the identified oil reserves of the world’s oil companies will ultimately be stranded in the ground to prevent climate change catastrophe. Might we now imagine a surge in sustainable energy demand that would cause the same result?

The negative price earlier this week concerned only contracts for delivery of barrels in May that are traded on the futures markets. Month-out futures contracts are selling at roughly $20 a barrel—suggesting that oil traders believe production will come back in line with demand. Crude exporters shut down 13% of the American drilling fleet, while Russia and the OPEC countries have agreed to reduce output by 9.7 million barrels a day. The White House has proposed paying U.S. frackers to keep their oil in the ground, but it can be costly to restart operations, and a shut oil facility might be damaged permanently. About all the government can do, currently, is lease space for an additional 47 million barrels in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. In the longer term, we can only hope for more concerted government support of continued alternative energy development.

Negative oil is obviously uncharted territory for the global economy and investment markets. Nobody seems to know what will happen except, perhaps, a tsunami of bankruptcies among oil drilling companies. The average price for a gallon of regular gasoline in the U.S. has fallen to $1.49, down a dollar from a year ago, but who today is filling up their tanks? Name brand companies like Exxon* and Chevron* are likely to see earnings declines, but in total, the oil and gas industry only makes up about eight percent of the U.S. gross domestic product—compared with 14 percent in the 1980s. The shock value of watching energy producers paying others to take oil off their hands could cause a temporary spike in stock market volatility among the startled herd of Wall Street traders, but for the rest of us, it’s back to social distancing, not driving much or flying, and watching with a bit of amazement as peak oil becomes negative oil: one more strange thing about this strange period in our lives. And, for SRI investors, whose portfolios are light or devoid of fossil fuel investments, it’s at least a bit comforting to see some out-performance on the downside.

Please stay safe and well.